You know that part in a heist movie where the heisters are poring over a map figuring out how to get into the bank vault? “What if we cut the power to the basement?” one of them suggests. “No, that won’t work,” another says, “because it will trigger the alarm system.” “Okay, then we’re going to have to shut down the alarm system from outside.” “But that will initiate a lockdown and we’ll be trapped.” “Hey,” says another, “what about this sewer line that runs under the bank?” They’ve found the way in! Time to see if they can pull it off.

That’s Cryptark.

However, Cryptark looks and certainly plays like a twin-stick shooter. It’s not top down, but it’s in zero-G so it might as well be. You fly a suit of space armor around a space dungeon shooting robots. You’re a salvager trying to loot a derelict space hulk that’s not quite derelict, because its defense systems are still active. Overall, this is very much a rogue-like. You’ll find new weapons, you’ll upgrade your space armor, and you’ll explore increasingly dangerous randomized space dungeons. When you die, you’ve totally lost all your stuff and now you have to buy new stuff. Which you were going to do anyway, so the real penalty is that you won’t get any reward for that space dungeon. And since the next set of space dungeons is harder, you’ve fallen behind the difficulty curve. Maybe not permadeath, but perma-gimp.

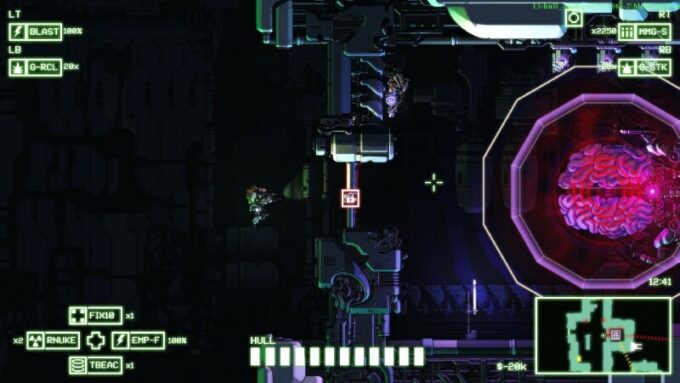

None of that stuff is unique. But Cryptark distinguishes itself for how the space dungeons aren’t dark inert dungeons. Instead, they are actively engineered to keep you at bay. Their automatic defense systems are sets of overlapping and interacting systems. Systems protecting systems protecting systems. Defensive guns, robot factories, alarms, shields, locked doors, sensor jammers, repair nodes. All of these protect the main core, which is your objective. Destroy the main core and the space hulk is yours to cash in.

You have 100% vision of the derelict (unless it’s got sensor jammers), including the locations and identities of all the robots. The plans are on the table for you to pore over. Disable this first, then that, then this, then move on the core. You’ve found a way in. Time to see if you can pull it off.

Most rogue-likes relying on discovery because they want to create a sense of exploration. What’s going to be in the next room? Where is the final boss? Which enemies will you fight? That’s why they take place in dungeons. A dungeon is underground and it doesn’t have windows. You can’t see into it. You don’t know which way it’s going to go. You don’t know if this is a dead end or the way to the next level. A dungeon is dark and mysterious. You can’t case the joint before you break in.

But these space hulks aren’t dungeons at all. You can see their shapes. You can see inside them. You know where everything is and how everything works. Cryptark doesn’t care about exploration. It cares more about your plan. It wants you to look at the map and decide which systems to shut down first. Before the twin-stick shootering, decisions will be made, options weighed, plans put forth. Ideally, it will be a quick in-and-out. Well, a quick in, since you win the instant you destroy the main core. You will find the unshielded exhaust port.

Before you play, you choose what weapons and equipment you’re bringing, which is part of the planning on any heist. This is the montage of close-ups where jumpsuits are zippered, hands are thrust into gloves, and guns are shucked into holsters. Load up on a shuttle floating just outside the space hulk. Once you leave, the shuttle door locks and you’re committed to whatever you suited up with. Cryptark is chock full of options. Stealth or firepower? What kind of firepower? Energy weapons or something with limited ammo? Which kind of machine gun? The shotgun? Or something that requires even less finesse, like the flamethrower? Grenades? What kind? A melee weapon? A shield? How much health? How many medkits? Skeleton keys? What items did you start with and what new stuff have you found? Do you need to save money? Because you can spend your way through some of Crytpark’s levels. Subvert the difficulty level, which sometimes isn’t even that difficult, with expensive hardware.

It reminds me of the very clever steampunk heist game The Swindle, which had a similar approach, but with 2D platformer gameplay. The procedurally generated levels in The Swindle were a real joy to plumb. Sometimes you just sneak in a window and there’s the loot! Other times you have to brave formidable defenses, trying and failing. Sometimes it’s really hard being a thief. Other times, it’s like stealing candy from a steampunk baby. But whereas The Swindle relied on the whims of its procedural generation, Cryptark relies on how its systems interact, and this is where you come in. You are disrupting a functioning defensive matrix. Where and how you disrupt it is up to you. Sometimes it’s really hard being a scavenger. Other times, it’s like stealing candy from a derelict space hulk baby. Imagine Invisible Inc. as a twin-stick shooter that lets you look at the whole level before you started, and that furthermore lets you choose where you want to enter. Or just imagine the open-ended options in the original Thief. Cryptark is that good.

When you start a game, you choose among four derelict ships. Win or lose, you then go to choose among four more difficult derelicts. Win or lose, you move on to yet four more harder derelicts. After doing this four times, you come to the hardest derelict space hulk of all. The Cryptark itself. It’s huge. It’s crammed with overlapping defenses. It’s sealed up tighter than a metaphor for something that’s really tight. And for me, it is impenetrable. I have repeatedly thrown myself into the Cryptark in three separate games and it has beaten me every time.

When I come across a locked door in a game with pre-built levels, like Thief or Dishonored or Prey, I have every confidence the designers have put the key somewhere outside the door. I trust they didn’t just lock the key inside and now I can’t beat the game. When I play a boss battle, I have every confidence the designers have given the boss a glowing orange weak point. I trust they didn’t cover it with armor. I don’t have that confidence about Cryptark’s hardest level. I look at the overlapping systems, how they protect and repair each other, and I see a mission impossible. I’m no Ethan Hunt. So I try and fail. At which point I can only try again as many times as I’ve earned money to rebuy my equipment. That’s the whole point of the early levels. To allow you to try the final level over again after failing. You’re basically gathering 1ups. Lives.

I shouldn’t complain, because Cryptark is letting me see the difficulty of the challenge. It’s not hiding anything. It’s showing me exactly how it’s not going to let me beat the last mission. If I take it at its word, if I can’t work out and execute a plan, that’s on me, right? Maybe I should spend more time farming the earlier levels for better equipment instead of just beating them?

Fortunately, there’s an open-ended mode that doesn’t throw a massive Cryptark in my face. I can keep playing increasingly hard dungeons, gathering equipment on the fly, hoping not to lose my one life. How far can I get? Cryptark could have released with just this mode and it would have been a fine game. However, in addition to this mode and the main mode (and local co-op!), there’s something called Cryptark excavation. I don’t know what it is. I must find out. But it won’t unlock until I beat the campaign. So here I come again to die in the eponymous Cryptark. Games this good are worth dying in.